I don’t have to tell you just how vital water is to survival; I’d be making a good bet if I put money on the square that says, “People generally know they die without access to water.” Even though most humans are lucky enough to have access to clean drinking water, knowing how water scarcity affects our bodies can save our lives and the lives of our families.

| Daily Water Consumed | Days to Live* |

|---|---|

| No Water | 3 – 6 days |

| 500 mL (16.9 oz) | 7 – 14 days |

| 1 L (33.8oz) | 15 – 30 days |

| 2L (67.7oz) | Indefinitely |

| *Based on average adult male at rest under favorable conditions | |

A person can live for about a week without water under ideal conditions. Environmental factors, health, age, and exertion will cause the body to lose water faster. A person can live for up to two weeks if only 16oz of water is consumed daily. A minimum of one quart of water per day is required to keep an average adult male hydrated for up to a month. A minimum of two quarts a day is needed to live indefinitely.

I’ve talked about storing water from an emergency preparedness perspective, but survival is a different animal. A freak situation could cut you off from your water stores at any time. We like to prep for earthquakes or other events that might happen, but what about fleeing from environmental disasters like flash floods or fires? Or finding yourself injured and stranded in the wilderness? Knowing how your body handles water and dehydration is key to survival.

What’s the minimum amount of water needed per day to survive?

Science doesn’t offer any firm answers on exactly how much water we need to survive daily. Scientists don’t test fatal levels of dehydration in a controlled experiment because, well, people would have to die to complete the experiment. That’s clearly not ethical.

And while we can tease out some information out of the current scientific research, too many factors play into hydration to know just how much water each person needs to drink to stay alive in a specific survival situation. Age, health conditions, climate, starting level of hydration, exertion, and body temperature can all affect how much water you need just to function at a basic level.1

We might not be able to predict the bare minimum amount of water we need to survive, but we know a few fundamental truths. An adult man in good health – let’s call him Average Guy – can live in a moderately dehydrated state for about four days before experiencing severe dehydration. A daily water intake of two cups can keep dehydration from reaching dangerous levels for an extended period. A full liter of water can keep even moderate dehydration at bay.

But there is a caveat – Average Guy is in a place where the temperature is just right, with no direct sun and no wind. And he doesn’t think about moving anywhere, either. We’re rarely Average Guy. In most cases, surviving a crisis means covering ground regardless of climate. It also calls for us to exert energy to build shelters, forage, hunt, and search for water that can be made safe.

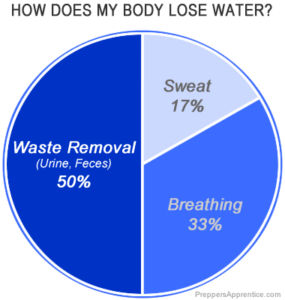

How does my body lose water?

A typical day would see us lose around three quarts of water, given that you are fully hydrated and not losing extra water to exercise, extreme temperatures, injury, or illness. We lose that water in three ways.

Breathing – Under normal circumstances, 33% of daily water loss is lost by exhaling air. Our lungs need to keep moisturized to function appropriately, but the constant contact with air combined with the warmth of our bodies leads to a lot of evaporation. Remember Average Guy? He’s losing about a quart of water just from breathing normally.

But survival situations keep us from being Average Guy. Other factors that increase the amount of water lost via breathing include temperature, humidity, and heightened cardiovascular movement.

Since lungs like moisture, it makes sense that humid air is a boon to them. If the air we breathe is already hydrated, less water is lost because our lungs aren’t working to stay hydrated – the water is already there.

But we can’t always benefit from humid air. In arid climates, we exhale moisture that our lungs need to stay hydrated, leading to an increase in overall water loss.

In freezing temperatures, our lungs react in a similar way to a dry climate. Our lungs lose more moisture during cold temperatures in the same manner. When the temperature falls below 10°F or -10°C, our exhalation turns from whisps to small clouds that trail us as we walk.

The last contributor to water loss via the lungs is cardiovascular movement. Once you get your heart rate up, your lungs demands more oxygen to feed your cells. That means more breaths per minute, often deeper and harder. Deeper, faster, harder breathing means more water exhaled.

Breathing through your nose, when possible, will keep the rate at which you exhale water down.

Skin – Average Guy is losing about 17% or about half a quart of his water from his skin. He’s in a nice, shady spot on a nice day. He’s going to stay there all day. Lucky guy.

But even if we are in a situation comparable to Average Guy, your skin will still use water. Our skin has a massive surface area, and like the lungs, needs to stay moist to function correctly. Moisture is naturally lost because it’s a water-permeable barrier.

Surviving means moving, and moving means sweating. You’re searching for a source of water. You’re hunting. You’re building out your camp or trying to cover as much ground as possible toward your destination. The weather is rarely perfect, and you know that when you are moving hard, sweat happens.

Extra sweating also happens when we’re overdressed or have a fever. Some illnesses and medications naturally cause us to sweat as well.

Body Waste – Day-to-day, this is where we expect to see our greatest loss. A hydrated person will have pee that’s mostly water. Our digestive system is incredibly good at reclaiming the water we use, so that’s usually okay. Captain Average can expect a daily loss of about 50%, or 1½ quarts. More if water is abundant and your kidneys are working to flush excess water out.

Survival situations can turn those numbers on their heads. Dehydration causes urine output to decline as your body starts to hold onto what it can. A virus or bacteria accidentally consumed can cause your digestive tract to strip water out of your reserves to flush out its attacker with a wicked case of diarrhea.

At a bare minimum, your kidneys will use about 16 oz of water a day if you’re not severely dehydrated.

What happens if you don’t drink enough water?

Your body will work hard to retain enough water to keep everything working, but as its level of hydration declines, some systems are slowed down or shut off in an effort to hoard what is left.

We usually think of thirst as our first real sign of dehydration, but by the time we experience a strong feeling of thirst, our bodies are well into the first stage of dehydration.

Long before we feel an intense thirst, we often feel hungry. Up to a third of our daily fluid intake comes from food, so our bodies naturally look for food as a source of hydration. This hunger-thirst feeling is well-known in the weight loss world, where tips to keep your water intake high are standard in almost all diets and fitness protocols.

When actual thirst is detected, often together with a dry mouth, your body is well on its way to moderate dehydration. Your body will soon take drastic action to hold on to what it has left.

The stages of dehydration

Dehydration starts when water loss exceeds consumption. That’s a pretty fine line, and we aren’t tuned in to our bodies enough to know where that line is. If left untreated, death is inevitable.

Before Mild Dehydration (~%2 of total body water volume loss)

You might feel hungry or munchy. This is your body’s first call for water. This is a natural reaction since we get a lot of water in our food. Your urine may be slightly more yellow than usual. You feel like you might not be up to performing strenuous physical activities.

Average Guy has lost about 800ml of water.

Mild Dehydration (~5% water loss)

The body is now actively pulling water out of places to use elsewhere. You are legitimately thirsty. While it’s evident that your mouth would become dry, more is happening behind the scenes.

Some cells in the brain begin to dehydrate. We become moody, our memory falters, and we probably get a little headache.2 We’re not sweating quite as readily as we might under normal circumstances because our skin is beginning to dry out.

Our muscles also start releasing water. Our blood pressure lowers because our blood is beginning to thin out. We generally feel tired, weak, and a little under the weather. We might feel lightheaded. Maybe we experience some muscle cramping. The body is telling us to slow down and conserve.

You aren’t urinating as much, and it’s a stronger yellow when you do.

Average Guy has lost about 2L of water.

Moderate Dehydration (~6% – 10% water loss)

This is where things get very uncomfortable. The body is working to maintain all systems at the lowest levels it can. We feel parched. Our eyes are dry and sinking into their sockets. Our lips crack, and our tongues might swell. Our skin has lost so much water that it has lost its elasticity and looks thin and wrinkly. The headache is so bad, and it’s killing our appetite. Our hands and feet feel cold, maybe even a little tingly.

Our blood pressure is so low that it might be hard to take our pulse at the wrist, but it’s shallow and rapid when we find it. We’re breathing rapidly as our lungs are drying out and working overtime to get oxygen to the heart. We might faint, or we might experience convulsions. Sometimes, we experience confusion and lose awareness for short periods.

We’re rarely urinating. Urine is very concentrated – a very dark yellow, almost orange.

Average Guy has lost between 2.4L and 4L of water.

Severe Dehydration (10% – 15% water loss)

It’s the body’s last stand. Systems slowly shut down to keep the brain, heart, and lungs going just a little longer. There’s a good chance that, if rescued, you could recover from severe dehydration with proper medical attention. But that’s if someone finds you – because you aren’t going anywhere on your own.

If you can urinate, it’s probably so dark, and it looks orange or maybe brown. The chances are good that your kidneys are shutting down.

The cardiovascular system has shut down almost entirely. Blood pressure is so low that you go into shock. Confusion, a delirious state of mind, and periods of unconsciousness make up most of the time you have left. Seizures are likely, and with enough of them, brain damage is certain.

Average Guy has lost 4 to 6 liters of water.

At 15% of water loss, death is imminent.

Should I ration water in a survival situation?

Rationing water in emergencies is not a good idea for many reasons.

We want to ration what we have because we feel we need to conserve just about everything when facing a crisis. But when water is in short supply, it is best to drink it. On the flip side, it’s counterproductive to overhydrate because your kidneys will quickly get rid of the excess.

If we’re talking about a small amount, like a 16oz bottle, consider it a road trip with a limited gas supply. You have 150 miles between you and the next gas station, an empty tank, and five gallons in the gas can. Giving the truck ‘sips’ of gas isn’t going to help you. If the tank can hold it, the gas should go into the tank, and then drive responsibly to make sure you can get as far as you can.

You function much better when fully hydrated than when not. Your cognitive skills begin to decline almost as soon as dehydration takes hold. It would be best to have a properly working brain to find the water needed.

The advice I see out there to take sips and wet lips is terrible. It’s wasting water. What are wet lips going to do for you? Make you feel better for five seconds? I get the psychological aspect of hoarding things in short supply, but it’s not rational in this case. Sipping water means you want to drink and are on the road to dehydration. Just drink it.

Water not consumed runs the risk of loss. A container can be lost or broken; water can spill, become contaminated, or evaporate. Things happen. When the last of your water ends up in the dirt, you make mud and nothing else except for maybe tears, which are incidentally also a poor use of water.

And if nothing else, keep the survival axiom about the Rule of 3’s in mind.

You can live for:

- Three minutes without air

- Three hours without shelter in extreme conditions

- Three days without water

- And three weeks without food

What are your chances of finding water in the next three days? Your dehydration level will be no different by the end of day three if you don’t find water, but your hydrated self might not make the same mistakes as rationing you could.

How can you minimize the water you need if stores are running low?

Staying hydrated in the first place, before an emergency takes place, will help. Drink as much water as your body needs every day, and then drink some more. A hydrated person will have more time on the clock to work through the stages of dehydration. Rationing the water you have in your body will also be much easier.

Stop eating when the water runs out. Because digesting carbs and protein requires water, it’s the one place you can store some of it in your body. But if you are out of water, digesting food will force your intestines to take it from other systems. In his book Basic Wilderness Survival Skills, Bradford Angier explains that when you eat, your kidneys use extra water to eliminate digestive waste.3

Work smarter, not harder. Whether you need to hike to your next location or build a base camp, expend your energy outside the day’s hottest hours. Also, don’t over-exert yourself. Between extra sweat, breathing, and heart pumping, the rate at which you lose water will be much greater than if you attack a job with a little less enthusiasm.

Don’t drink questionable water, and don’t eat questionable food. That stream might look crystal clear, but drinking water contaminated with microscopic parasites or bacteria can be life-threatening in emergency scenarios. Diarrhea and vomiting brought on by a case of dysentery or giardiasis can use up your internal water stores very quickly.

Sources

- Dehydration, MayoClinic.org. Overview of symptoms, causes, risk factors, complications, and prevention of dehydration ↩︎

- Recognizing a Dehydration Headache, HealthLine.com. Information on how to recognize and treat a dehydration headache ↩︎

- pp 94-96, Basic Wilderness Survival Skills, 2002, Bradford Angier. Detailed guidebook on surviving in the wild ↩︎